Prion, which is an abnormal form of a normally harmless protein found in the brain that is responsible for a variety of fatal neurodegenerative diseases in animals, including humans, is called transmissible spongiform encephalopathies.

In the early 1980s, American neurologist Stanley B. Prusiner and his colleagues identified the “infectious protein particle,” a name that was shortened to “prion” (pronounced “pree-on”). Prions can enter the brain through infection or can arise from mutations in the gene that codes for the protein.

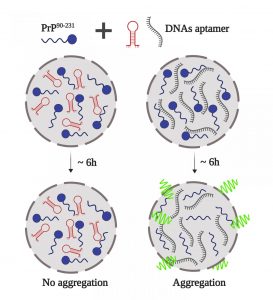

Once present in the brain, prions multiply by inducing benign proteins to fold into an abnormal shape. This mechanism is not fully understood, but another protein normally found in the body may also be involved. Normal protein structure is thought to consist of a series of flexible coils called alpha-helices. In prion protein, some of these helices are stretched out into flat structures called beta-strands.

The normal conformation of the protein can be degraded quite easily by cellular enzymes called proteases, but the prion protein form is more resistant to this enzymatic activity. Therefore, as prion proteins multiply, they are not broken down by proteases and instead accumulate inside neurons, destroying them. The progressive destruction of neurons eventually causes brain tissue to fill with holes in a sponge-like or spongiform pattern.

Prion diseases that affect humans include: Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, Gerstmann-Sträussler-Scheinker disease, fatal familial insomnia, and kuru. Prion diseases that affect animals include scrapie, bovine spongiform encephalopathy (commonly called mad cow disease), and chronic wasting of mule deer and elk.

For decades, doctors thought these diseases were the result of infection with slow-acting viruses, named for the long incubation times required for the diseases to develop. These diseases were called, and are sometimes still called slow infections. The pathogen of these diseases has certain viral attributes, such as extremely small size and strain variation, but other properties are atypical of viruses. In particular, the agent is resistant to ultraviolet radiation, which normally inactivates viruses by destroying their nucleic acid.

Prions differ from all other known disease-causing agents in that they appear to lack nucleic acid, that is, DNA or RNA, which is the genetic material that all other organisms contain. Another unusual feature of prions is that they can cause hereditary, infectious and sporadic diseases; for example, Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease manifests itself in all three forms, with sporadic cases being the most common.

Prion proteins can act as infectious agents, spreading disease when transmitted to another organism, or they can arise from an inherited mutation. Prion diseases also show a sporadic pattern of incidence, meaning that they appear to appear randomly in the population. The underlying molecular process that causes the prion protein to form in these cases is unknown. Other neurodegenerative disorders, such as Alzheimer’s disease or Parkinson’s disease, may arise from molecular mechanisms that result in protein misfolding that are similar to those that cause prion diseases.

Types of prion diseases

Prion disease can occur in both humans and animals. Below are some different types of prion diseases.

Human prion diseases

- Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD). First described in 1920, CJD can be acquired, inherited, or sporadic. Most CJD cases are sporadic.

- Variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (vCJD). This form of CJD can be acquired by eating the contaminated meat of a cow.

- Fatal familial insomnia (FFI). FFI affects the thalamus, which is the part of your brain that manages your sleep-wake cycles. One of the main symptoms of this condition is worsening insomnia. The mutation is dominantly inherited, meaning an affected person has a 50 per cent chance of passing it on to their children.

- Gerstmann-Straussler-Scheinker syndrome (GSS). GSS is also inherited. Like FFI, it is dominantly transmitted. It affects the cerebellum, which is the part of the brain that handles balance, coordination, and equilibrium.

- Kuru: Kuru was identified in a group of people from New Guinea. The disease was transmitted through a form of ritual cannibalism in which the remains of deceased relatives were consumed.

Risk factors for these diseases include:

- Genetics. If someone in your family has an inherited prion disease, you are also at higher risk of having the mutation.

- Years. Sporadic prion diseases tend to develop in older adults.

- Animal products. Eating animal products that are contaminated with a prion can give you a prion disease.

- Medical procedures. Prion diseases can be transmitted through contaminated medical equipment and nerve tissue. Cases, where this has happened, include transmission through contaminated corneal transplants or dura mater grafts.

What are the symptoms of prion disease?

Prion diseases have very long incubation periods, often on the order of many years. When symptoms develop, they get progressively worse, sometimes rapidly. Common symptoms of prion disease include:

- difficulties with thinking, memory, and judgment

- personality changes such as apathy, agitation, and depression

- confusion or disorientation

- involuntary muscle spasms (myoclonus)

- loss of coordination (ataxia)

- difficulty sleeping (insomnia)

- difficult or slurred speech

- vision problems or blindness

How is prion disease treated?

There is currently no cure for prion disease. But treatment focuses on providing supportive care. Examples of this type of care include:

- Medications: Some medications may be prescribed to help treat symptoms. Examples include:

– reduce psychological symptoms with antidepressants or sedatives

– providing pain relief using opiate medications

– relieve muscle spasms with drugs such as sodium valproate and clonazepam

- Assistance. As the disease progresses, many people need help to care for themselves and do their daily activities.

- Providing hydration and nutrients. In the advanced stages of the disease, intravenous fluids or a feeding tube may be required.